What is Strategic Stability?

Strategic stability describes a state of affairs that aims to minimize all types of risks of deterrence failure.

It can be understood as a state in which the postures, capabilities and doctrines of nuclear-armed states do not incentivize the first-use of nuclear weapons in a crisis (crisis stability); in which those states have an assured retaliatory capability; and in which they do not improve their relative position by increasing strategic arsenals qualitatively or quantitatively (arms race stability). Strategic stability concerns not only the nuclear domain, but also space, cyber and advanced offensive and defensive conventional weapon systems.

During the Cold War, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev agreed “that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

Today, this statement is once again relevant. It should serve as a reminder that strategic stability, if implemented correctly, can help stabilize international relations, and thus strengthen peace and security.

-

Andrey BaklitskiyAndrey Baklitskiy is Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Advanced American Studies at the Institute of International Studies of the MGIMO University of the Russian Foreign Ministry and a Consultant at PIR Center. His areas of expertise include nuclear arms control, nuclear non-proliferation, Iranian nuclear program, US-Russian strategic relations.

Andrey BaklitskiyAndrey Baklitskiy is Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Advanced American Studies at the Institute of International Studies of the MGIMO University of the Russian Foreign Ministry and a Consultant at PIR Center. His areas of expertise include nuclear arms control, nuclear non-proliferation, Iranian nuclear program, US-Russian strategic relations. -

Dr. Corentin BrustleinCorentin Brustlein was, until April 2021, the Director of the Security Studies Center at the French Institute of International Relations in Paris. He has been a member of the Advisory Board for Disarmament Matters to the UN Secretary-General since 2018 and holds a PhD in political science from the Jean Moulin University of Lyon. He participated in the KSSI in a strictly personal capacity.

Dr. Corentin BrustleinCorentin Brustlein was, until April 2021, the Director of the Security Studies Center at the French Institute of International Relations in Paris. He has been a member of the Advisory Board for Disarmament Matters to the UN Secretary-General since 2018 and holds a PhD in political science from the Jean Moulin University of Lyon. He participated in the KSSI in a strictly personal capacity. -

Dr. Samuel CharapDr. Samuel Charap is a Senior Political Scientist at the RAND Corporation, based in RAND’s Washington, DC office. His research interests include the political economy and foreign policies of Russia and the former Soviet states; European and Eurasian regional security; and US-Russia deterrence, strategic stability and arms control.

Dr. Samuel CharapDr. Samuel Charap is a Senior Political Scientist at the RAND Corporation, based in RAND’s Washington, DC office. His research interests include the political economy and foreign policies of Russia and the former Soviet states; European and Eurasian regional security; and US-Russia deterrence, strategic stability and arms control. -

Dr. Liana FixLiana Fix is Programme Director for International Affairs at Körber-Stiftung’s Berlin office. Previously, she was affiliated with the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) and the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). Her areas of expertise include Russia and Eastern Europe, EU-Russia relations, German Foreign Policy, and European Security.

Dr. Liana FixLiana Fix is Programme Director for International Affairs at Körber-Stiftung’s Berlin office. Previously, she was affiliated with the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP) and the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP). Her areas of expertise include Russia and Eastern Europe, EU-Russia relations, German Foreign Policy, and European Security. -

Christoph HeilmeierChristoph Heilmeier is a Programme Manager for International Affairs at Körber-Stiftung. His areas of expertise include German foreign policy, U.S. politics and transatlantic relations as well as digitalisation and foreign policy.

Christoph HeilmeierChristoph Heilmeier is a Programme Manager for International Affairs at Körber-Stiftung. His areas of expertise include German foreign policy, U.S. politics and transatlantic relations as well as digitalisation and foreign policy. -

Prof. Han HuaHan Hua is Associate Professor and Director of the Center for Arms Control and Disarmament at the School of International Studies (SIS), Peking University, China. Her research interests cover nuclear-related deterrence and strategic stability both in regional and global perspectives. She has led programs and projects on those areas.

Prof. Han HuaHan Hua is Associate Professor and Director of the Center for Arms Control and Disarmament at the School of International Studies (SIS), Peking University, China. Her research interests cover nuclear-related deterrence and strategic stability both in regional and global perspectives. She has led programs and projects on those areas. -

Dr. Ulrich KühnDr. Ulrich Kühn leads the research area “Arms Control and Emerging Technologies” at IFSH and is a Non-Resident Scholar with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His research focuses on arms control and non-proliferation mechanisms, nuclear and conventional deterrence, Euro-Atlantic and European security, and international security institutions.

Dr. Ulrich KühnDr. Ulrich Kühn leads the research area “Arms Control and Emerging Technologies” at IFSH and is a Non-Resident Scholar with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His research focuses on arms control and non-proliferation mechanisms, nuclear and conventional deterrence, Euro-Atlantic and European security, and international security institutions. -

Dr. Dmitry SuslovDmitry V. Suslov is a Deputy Director at the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies, National Research University – Higher School of Economics, as well as a Deputy Director for Research at the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy. He conducts research and consults the Russian government and business on the US Foreign Policy and US-Russia relations, Russia-EU relations, and Russian Foreign Policy.

Dr. Dmitry SuslovDmitry V. Suslov is a Deputy Director at the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies, National Research University – Higher School of Economics, as well as a Deputy Director for Research at the Council on Foreign and Defense Policy. He conducts research and consults the Russian government and business on the US Foreign Policy and US-Russia relations, Russia-EU relations, and Russian Foreign Policy. -

Dr. Heather WilliamsDr. Heather Williams is a Lecturer (Associate Professor) at King's College London. She is also an Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) and a Senior Associate Fellow with the European Leadership Network. From 2018 to 2019 Dr. Williams served as a Specialist Advisor to the House of Lords International Relations Committee inquiry into the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and Disarmament.

Dr. Heather WilliamsDr. Heather Williams is a Lecturer (Associate Professor) at King's College London. She is also an Associate Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) and a Senior Associate Fellow with the European Leadership Network. From 2018 to 2019 Dr. Williams served as a Specialist Advisor to the House of Lords International Relations Committee inquiry into the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and Disarmament. -

Tong Zhao, PhDTong Zhao is a senior fellow at the Carnegie–Tsinghua Center for Global Policy in Beijing. His research focuses on strategic security issues, such as nuclear weapons policy, deterrence, arms control, nonproliferation, missile defense, and hypersonic weapons. His current research focuses on possible future arms control options for the major powers.

Tong Zhao, PhDTong Zhao is a senior fellow at the Carnegie–Tsinghua Center for Global Policy in Beijing. His research focuses on strategic security issues, such as nuclear weapons policy, deterrence, arms control, nonproliferation, missile defense, and hypersonic weapons. His current research focuses on possible future arms control options for the major powers.

James M. Acton,

“Escalation through Entanglement”,

International Security, Vol. 43, No. 1, Summer 2018.

Andrey A. Baklitskiy,

“High-Precision Long-Range Conventional Systems and their Impact on Strategic Stability”,

PIR Center.

Andrey A. Baklitskiy, Tong Zhao and Alexandra Bell,

“To Reboot Arms Control, Start with Small Steps” - “Архитектура контроля над вооружениями разрушается на наших глазах”,

Kommersant, September 17th 2020.

Corentin Brustlein,

“Strategic Risk Reduction between Nuclear-Weapons Possessors”,

IFRI Proliferation Papers, No. 63, January 2021.

Samuel Charap, Alice Lynch, John J. Drennan, Dara Massicot, and Giacomo Persi Paoli,

“A New Approach to Conventional Arms Control in Europe: Addressing the Security Challenges of the 21st Century”,

RAND Research Report, 2020.

Han Hua,

“China’s proper role in the global nuclear order – A Chinese response”,

Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, Vol. 73, Issue 2, March 4th 2017.

Sergei A. Karaganov, Dmitry V. Suslov,

“The New Understanding and Ways to Strengthen Multilateral Strategic Stability”,

Higher School of Economics National Research University Report, 2019.

Patricia M. Kim (ed.),

“Enhancing US-China Strategic Stability in an Era of Strategic Competition. US and Chinese Perspectives”,

United States Institute of Peace, Report No. 172, April 2021.

Heather Williams,

“Asymmetric arms control and strategic stability: Scenarios for limiting hypersonic glide vehicles”,

Journal of Strategic Studies, Vol. 42, August 22nd 2019.

Heather Williams,

“Remaining relevant: Why the NPT must address emerging technologies”,

King’s College London Report, August 2020.

Tong Zhao,

“Conventional Long-Range Strike Weapons of U.S. Allies and China’s Concerns of Strategic Instability”,

The Nonproliferation Review, September 14th 2020.

IFSH Hamburg,

“Sicherheitspolitik einfach erklärt. Drohnen und autonome Waffen - Fluch oder Segen?”, YouTube,

(video in German with English subtitles)

IFSH Hamburg,

“Sicherheitspolitik einfach erklärt. Was passiert, wenn eine Atombombe explodiert?”, YouTube,

(video in German with English subtitles)

IFSH Hamburg,

“Sicherheitspolitik einfach erklärt. Wettrüsten: Dunkle Vergangenheit oder aktuelle Gefahr?”, YouTube,

(video in German with English subtitles)

B-52H Stratofortress releasing flares over the Indian Ocean, Feb-19-2020, edited photo on base of license Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Photo: Mizzoujp, Source

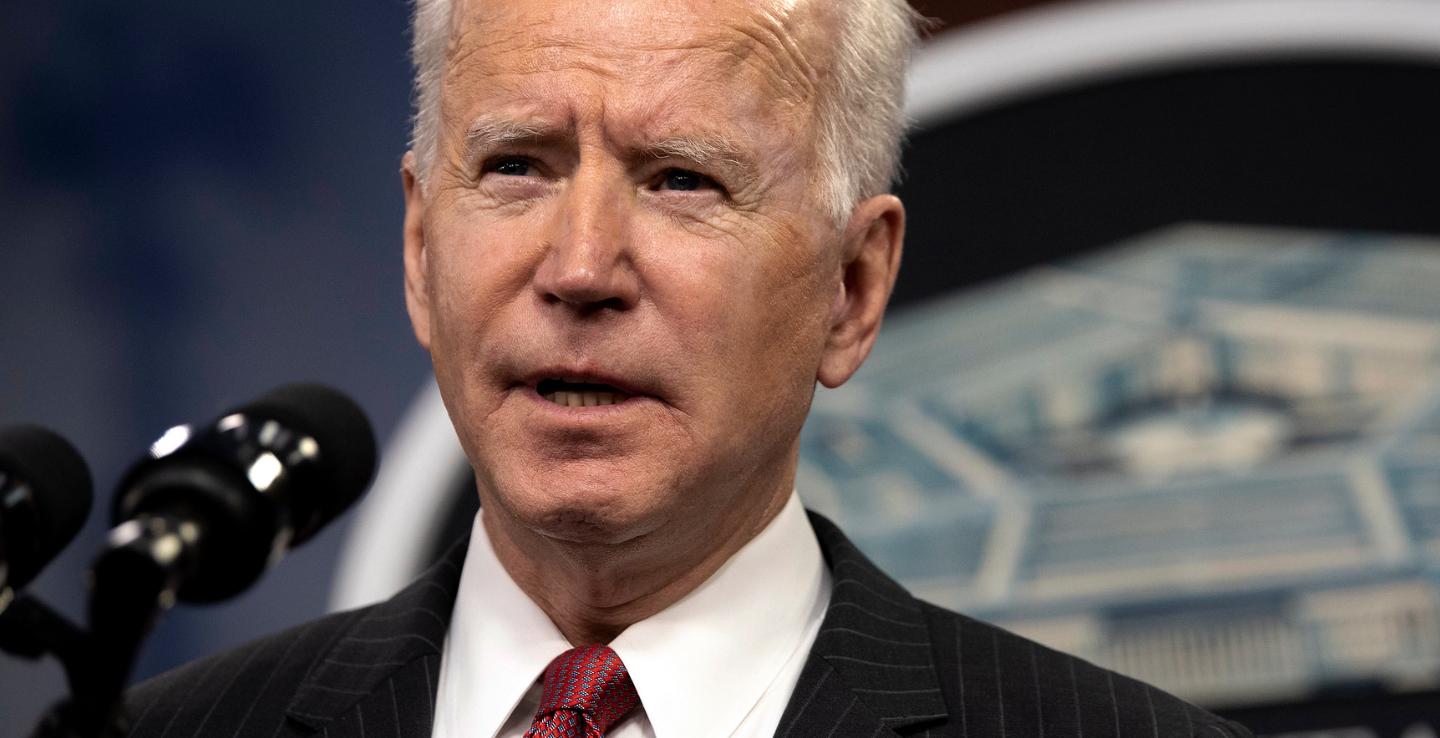

Joseph R. Biden, President Joseph R. Biden at the Pentagon, Feb-10-2021.

Photo: DoD / Lisa Ferdinando, Source

Vladimir V. Putin, President Vladimir V.Putin addresses the Federal Assembly, Jan-15-2020.

Photo: kremlin.ru, Source

Xi Jinping, President Xi Jinping reviews troops of the People's Liberation Army, Jun-30-2017.

Photo: Anthony Kwan / Bloomberg via Getty Images, Source

Missile combat crew on alert in underground launch control center, monitoring Minuteman ICBMs, Aug-18-2006.

Photo: United States Air Force, Source

Chinese People's Liberation Army soldiers regarding DF-1 missile at Military Museum in Beijing, Dec-6-2004.

Photo: Frederic J. Brown / AFP via Getty Images, Source

Missile maintenance crewmen perform electrical check on a Minuteman III ICBM, Jan-1-1980.

Photo: DoD / Defense Visual Information Center, Source

1987, Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan sign INF Treaty, Dec-8-1987.

Photo: White House Photographic Office, Source

2011, Barack Obama and Dmitry Medvedev sign New START Treaty, Apr-8-2010.

Photo: Getty Images, Source

2018/2019, DF-17 missile system, which can carry a hypersonic glide vehicle, at military parade in Beijing, Oct-1-2019.

Photo: Frederic J. Brown / AFP via Getty Images, Source

2019, U.S. flight test of a ground-launched cruise missile, Aug-18-2019.

Photo: Scott Howe, Source

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)